Graham Road - Credit: Archant

This week marks 15 years since the bloody culmination of a two-week siege that ground a Hackney street to a halt. The Gazette looks through the archive and speaks to those who played major roles in the drama to find out what they remember about January 2003 in Graham Road.

Eli Hall. - Credit: Archant

The name Eli Hall won’t mean much to Hackney newcomers, but 15 years ago the whole country was watching his Graham Road home during what would be Britain’s longest ever siege.

Up to 150 cops were stationed outside the gunman’s bedsit for 15 days after he barricaded himself inside with a 22-year-old student as a hostage.

Despite police employing a patient approach, determined to avoid bloodshed, the stand-off ended with Hall putting a bullet through his brain.

The siege also left 22 neighbouring families unable to go home for a fortnight, with some put up in the plush Hilton hotel in Angel and others left in hostels. Thirty-two more who were escorted home under armed guard had to be brought food parcels and medication by town hall staff.

The chaos began on Boxing Day morning, 2002, when officers spotted a Toyota Celica with foreign plates in Marvin Street, which connects Graham Road and Sylvester Road.

The car was linked to an incident in Old Compton Street, Soho, and another on the Downs Estate in the preceding months, both of which resulted in police being shot at.

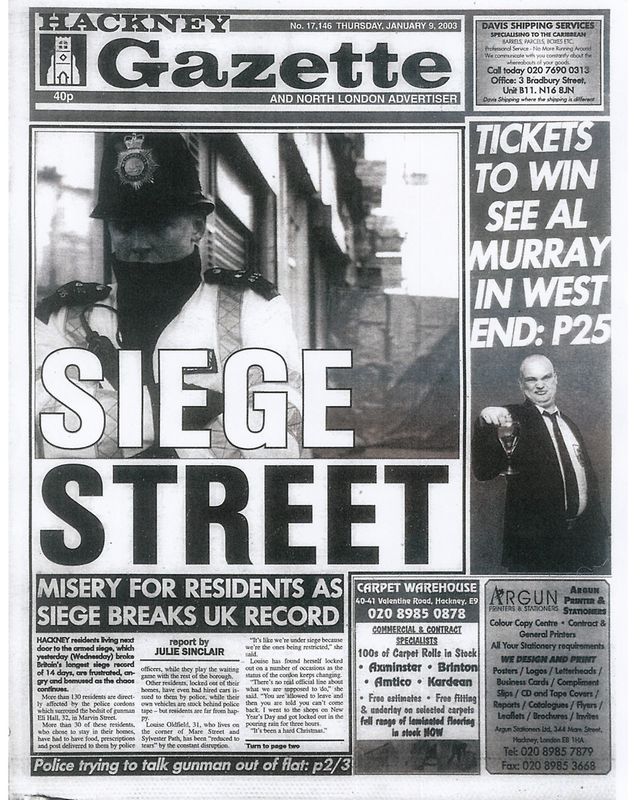

Credit: Archant

Cops sent for it to be towed, and had armed officers as back up. But Hall threatened the contractor and then shot at officers as they tried to get him to come outside.

In the days that followed, Met negotiator Det Ch Insp Sue Williams tried to reason with Hall and urged him to give himself up, but he repeatedly insisted he was never going “back to prison”. He fired on police several times throughout the siege.

“Everyone involved in that siege wanted him to come out alive,” Sue, now working as a kidnap negotiator, told the Gazette this week. “When he didn’t, it had an incredibly negative and sad feeling on all of us.

“Every time he said something like ‘you won’t take me alive’ or ‘I’m not going back to prison’, we would challenge it. He did a lot of talking. He was very mercurial.”

Police tried everything to appeal to the gunman, but couldn’t.

“We went to see Eli’s partner and brother, who were both in prison, to see if we could get some leverage but it felt like there was nothing important enough for him,” said Claudine Duberry, who as chair of Hackney’s Independent Advisory Group was drafted in by police to keep the community abreast of the situation.

Credit: Archant

Tony, of Tony’s Cafe, underneath his flat, told the Gazette this week Hall was a regular.

“He was a customer in here – chubby,” he said. “He’d been coming in since I opened it a year before.

“He’d have scrambled eggs and onions on toast. He was quiet. He’d sit in that corner over there and read the paper from cover to cover.”

Hostage negotiator

Det Ch Insp Sue Williams, a hostage negotiator for the Met and the FBI since 1991, was tasked with talking to Eli Hall.

Now helping out governments and companies in the world’s kidnap hotspots, Sue told the Gazette her overriding memory of the siege was the freezing conditions.

“I remember it was really cold,” she said. “We didn’t know how long it was going to go on for and we were inconveniencing the community and police staff as well because it was Christmas.

“I also remember some of the council people we needed to speak to reminding us it was the wrong time of year.

“The investigating officer was Bob Quick, or B. Quick, so that was mentioned a few times.

“The siege did present a lot of challenges because of the fact we disrupted so many people’s lives. There was a lot of shouting at the cordons, and not necessarily words of encouragement.”

Community reacts

The drama of the country’s longest ever siege taking place in Hackney was understandably lost on those unable to go home because of it, as well as traders who lost two weeks’ worth of income.

“It’s like we’re under siege because we’re the ones being restricted,” said Louise Oldham after two weeks of it. “There’s no official line about what we are supposed to do. I went to the shops on New Year’s Day and got locked out in the pouring rain for three hours. It’s been a hard Christmas.”

A public meeting at the town hall five days after the siege ended gave neighbours the chance to grill then-mayor Jules Pipe.

“Does the council even have an emergency plan?” one asked. Complaints ranged from a lack of sleep and a lack of information to loss of business and being forced to stay in hostels.

“What’s the point in putting us in emergency accommodation with no kettle and giving us Cup-a-Soup?” Gillian Rooney, who lived opposite Hall’s flat, queried.

The siege cost the cops £1million once the council had billed the Met £50,000 for the cost of provisions, hostels and rooms at the Islington Hilton.

Shopkeepers in Graham Road also wrote to Tony Blair asking for compensation for the loss of trade, but heard nothing.

“We didn’t get a penny,” said Tony, of Tony’s Cafe. “All 18 shops were closed. We wrote to the prime minister, everyone. Nothing.”

The cops were unpopular for taking a “softly-softly approach” – characterised by the takeaways – that left neighbours frustrated and angry. Hackney borough commander Ch Supt Derek Benson apologised soon after it ended for the chaos caused.

He said: “I appreciate this is a bit late, but I am sorry. It was never our intention to let anyone down.”